Bruce Campbell

What if you could see the ocean through the eyes of someone who’s spent more than 40 years in and around water — not just skimming the surface, but diving deep into its hidden worlds?

Water has shaped my life from the very beginning. I started swimming at age six, competing by seven, and was soon ranked among the top sprint swimmers in Colorado. In high school, I began coaching younger swimmers and lifeguarding — roles that helped pay my way through college.

After law school, I built a career defending attorneys and competed in over 40 triathlons — including one where I beat Lance Armstrong before his return to racing in Europe. But it was in my 40s that everything shifted. I took up scuba diving, and the ocean transformed from a training ground into a living, breathing canvas.

Julian’s creative process is rooted in observation and stillness. From aerial cityscapes to minimal brushwork on raw canvas, each collection reflects a quiet complexity that invites introspection. His work has been showcased in private collections and contemporary galleries across Europe and North America.

“The sea, the great unifier, is man’s only hope. Now, as never before, the old phrase has a literal meaning: we are all in the same boat.” Jacques Cousteau

MEET THE ARTIST

About Me

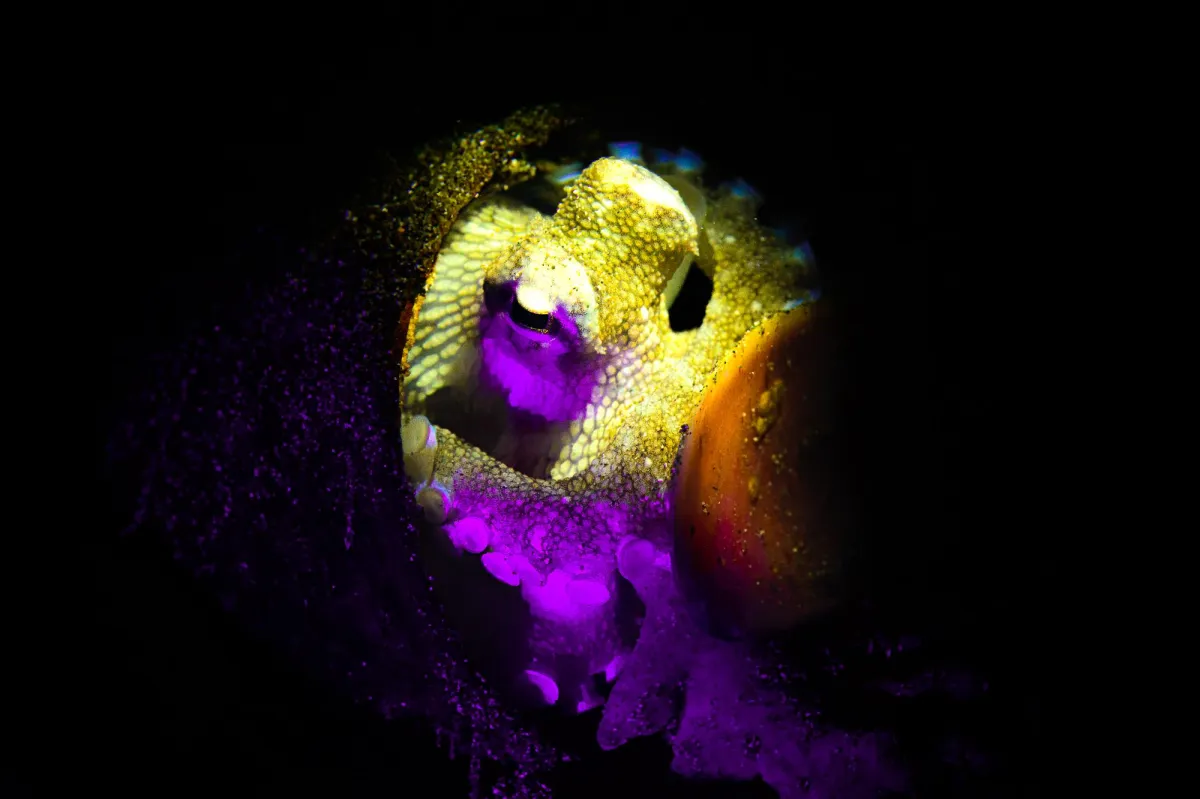

The sea casts its spell and inspires my art.

“I create large-format works to offer viewers more than just a glimpse—I want them to step into the frame, to feel the energy, the silence, and the pulse of the moment as I did when capturing it.”

As Julian Arlen’s creative journey has taken him across continents—from the bustling streets of Marrakech to the serene coastlines of Iceland, and the quiet temples of Kyoto—he’s uncovered patterns, textures, and emotions that transcend geography. His work bridges the divide between what we recognize and what we feel, transforming familiar landscapes into abstract visions that invite deeper reflection.

Through the interplay of light, shadow, and form, Julian’s images reveal hidden dimensions, challenging us to see not just the world, but our place within it, differently. Each piece becomes a window into another perspective, offering collectors and viewers an experience that lingers long after the moment has passed.

THE PROCESS

Bringing an idea to life through the art of underwater photography begins long before the first shutter click.

Before I fly to any of the many reefs where I have created images, I have reviewed what species of animals have been found in the location and have studied their natural habitat. I have considered the corals and sponges if any that may exist in the habitat. I typically will mull over how I want to create the images I hope to make.

Every dive begins with a decision that shapes the entire day’s work — one that cannot be undone once I enter the water. I must choose whether to shoot with a wide-angle or a macro lens. There is no “one-lens-fits-all” solution for underwater photography, and lenses cannot be changed once submerged. This choice determines not only the style of imagery I can capture but often whether a once-in-a-lifetime encounter becomes an image — or simply a memory.

One of my recurring nightmares is descending with my macro setup and then watching a humpback whale glide into view. Encounters like that are extraordinarily rare, commanding awe and presence. Yet, with the wrong lens, the most I can capture might be the detail of an eye or the texture of barnacles on a fin — beautiful, but hardly the sweeping portrait such a subject deserves.

Before any dive, setting up the housing, strobes, modifiers, and lenses can take an hour or more. Once assembled, I place the camera under a vacuum seal for several hours to ensure it’s watertight. Any leak would not only destroy that day’s work but potentially end photography for the remainder of the expedition — since carrying backup systems on remote dives is nearly impossible.

Limited Edition Only!

Collector’s Prints for the Discerning Collector

My fine art photography works are crafted to spark conversation and captivate the imagination. Each piece is available in exclusive, limited editions—ensuring your collection remains unique and timeless.

From private residences to corporates, his images grace walls around the globe, bringing depth, emotion, and refined elegance to every space.

Invest in artwork that transforms your environment and resonates for years to come.

VIP INSIDER

Become a VIP Insider. The images I bring back are rare. The ones who see them first? My private collectors.

Your email address will never be shared with a third party without your written permission.

Step Into New Dimensions of Art and Perspective

Step into a world where every piece tells a story.